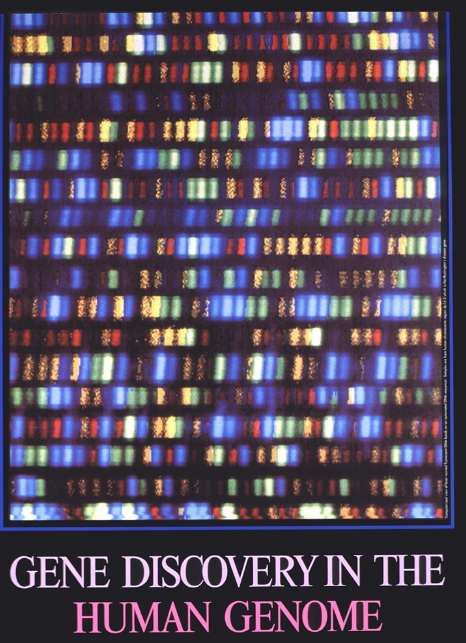

25 Years of the Human Genome Project: Unlocking Life’s Code and Imagining the Next Frontier

Twenty-five years ago, an extraordinary milestone was reached in science and medicine: the first full draft of the human genome was completed. The announcement marked the culmination of a decade-long international effort involving over a thousand scientists across six countries, decoding nearly all three billion letters of our DNA—the master code of life.

Back then, the promises were as bold as they were ambitious: a revolution in diagnosing, preventing, and curing diseases like Alzheimer’s, cancer, and diabetes by targeting their genetic roots. While some hopes were premature, the reality has been a story of steady, remarkable progress—and an even more exhilarating future.

From Skepticism to Sequencing: The Origins of the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was not always met with universal enthusiasm. In the 1980s, critics argued it would siphon funds from smaller research efforts or yield uninteresting data. Some believed much of our genome was "junk" and thus unworthy of exploration. Others raised concerns about genetic discrimination.

However, the U.S. Department of Energy championed the initiative to understand radiation's effects on DNA, and with support from Congress, the HGP officially launched in 1990. A decade later, in 2000, President Bill Clinton heralded the completion of the first draft with words that captured the magnitude of the moment: “Today, we are learning the language in which God created life.”

Breakthroughs and Reality Checks

Expectations were sky-high. Scientists predicted 100,000 protein-coding genes in humans; they discovered just 20,000—about 2% of our genome. The remaining 98%? Far from junk, this so-called non-coding DNA holds crucial regulatory functions that are now better appreciated thanks to post-genomic research.

Major gains have indeed been made:

- Cancer and rare disease diagnostics have been transformed.

- Genomic insights into human evolution have deepened.

- CRISPR gene editing emerged as a powerful tool, with the first personalized CRISPR therapy recently administered to an infant with a genetic disorder.

- Drug development is being reshaped through genomics-informed design.

Yet, many mysteries remain. Vast portions of the genome are still not fully understood, and the benefits of this knowledge have not yet been equitably distributed globally.

The Genomic Future: What’s on the Horizon?

What might the next 25 years bring?

- Whole Genome Sequencing at Birth

In the UK, plans are underway to offer genome sequencing for every newborn within a decade. The goal: early detection of hundreds of genetic conditions, enabling timely interventions.

- Pharmacogenomics

Also known as "precision prescribing," pharmacogenomics examines how genetic differences affect drug responses. Embedding this into routine care could ensure the right medication—and dose—is given the first time.

- Predictive Medicine and Multi-Omics

Understanding how genes, environment, metabolism, and lifestyle interact (termed "multi-omics") could help predict disease risks and tailor lifestyle or medical interventions before symptoms arise.

- AI-Powered Genomic Insights

AI is poised to accelerate discoveries by identifying hidden patterns in complex datasets, such as linking specific gene variants to diseases, drug responses, or even predicting cellular behavior—leading to more precise and efficient therapies.

- Virtual Cells and Drug Design

Through "synthetic and generative genomics," scientists aim to design proteins or entire cells not found in nature. AI-generated DNA sequences could lead to entirely novel medicines, industrial enzymes, or environmental solutions.

Ethical Crossroads: Genetic Equity and Responsibility

With great power comes great responsibility. As genome sequencing becomes routine:

- Privacy and data security must be safeguarded.

- Access disparities must be addressed—such as the $2 million CRISPR therapy for sickle cell disease, inaccessible to most in sub-Saharan Africa where the disease burden is highest.

- Ethical limits of genetic editing must be debated—what constitutes a "fault" worth correcting, and who decides?

These questions demand robust global dialogue.

A New Era of Biology

As we stand on the cusp of designing biology itself, the Human Genome Project remains a testament to human curiosity and cooperation. We’ve gone from merely reading the code of life to rewriting it. From decoding DNA to designing the future.

To paraphrase Professor Matt Hurles of the Sanger Institute: it took four billion years for life to evolve its current diversity; we may decode all of it in just forty. The next generation of scientists, ethicists, and clinicians—including child neurologists—will play a critical role in ensuring this genomic revolution serves humanity, equitably and wisely.